In the opening of this series, I talked about how popular culture influenced us because it’s all around us. I talked about how it becomes the elephant in the room because of that. But what I didn’t talk about was how popular culture fits into our battle to change harmful cultural paradigms. And, really, that’s a glaring oversight that I intend to correct right now.

You see, I came across a post today (… oy. by Julia) that gave me one of those headsmacking, “OH!” moments. Not because I agree with her — far from it, I’m about to spend this entire post rebutting the points that she made — but because I finally understand the basis for the argument that [x] concern needs to be shelved so [y] and [z] concern can be taken care of first.

I. Chicken or the Egg Syndrome

So much of what happens in comics seems to be based on predispositions of society. The sexualization won’t really change until society changes and doesn’t, as a whole, view it as being so acceptable.

I’m not going to dispute Julia’s assertion that “much of what happens in comics seems to be based on predispositions of society,” because, well, I agree. Popular culture draws its themes, plots, dialogue, stereotypes, and all that other good stuff from our existing culture. Nothing exists in a vacuum, and it would be naive to pretend that the treatment of women in comics/movies/etc. is self-contained.

But, at the same time, nothing exists in a vacuum. Popular culture doesn’t just draw from society, it is part of what shapes it. Popular culture has been around as long as societies have existed — being inspired by, reinforcing, and ultimately shaping society. Because of this, presenting the problem as linear — “culture –> popular culture” — is misleading. The reality is that the relationship is a circle, with popular culture influencing society and society in turn influencing popular culture.

II. Debunking the “Cause-Effect” Theory

Simply stated, my issue is with the cause and not the effect, because the effect will not dissipate until the cause is eliminated. I would truly like to see things change! But in order for that to happen the root of the problem has to be attacked, and that root is so large that it will take decades, probably, even with all the troops called in (and hopefully behaving themselves).

Bearing in mind what I said in Section I, I’d like to now turn to Julia’s argument that her “issue is with the cause and not the effect, because the effect will not dissipate until the cause is eliminated.” Well, it should come as no surprise that I disagree with the way in which she chose to frame the issue. Here again, I have to say that the “cause-effect” relationship she sets up is misleading because it oversimplifies the issue.

What root of which problem? The sexualization of women? Well, that’s just one facet of the oppression that women face. The patriarchy? Two problems there: 1) it’s an abstract concept, not a concrete problem to be solved, and 2) it supposes that gender inequity is the root of all oppression. Even if you use the word as I sometimes do, as a feminist shorthand for the oppressive institutions that legitimize hierarchies of power, “fighting oppression” is a starting point, not a path to success.

There is no concrete “root” because the problem of oppression intersects all kinds of different cultures. And, frankly, the group who we often think of as our feminist foremothers didn’t just fail to solve the problem of oppression because they didn’t have enough time, but because their idea of what the “root of all oppression” was too narrow. You can’t solve oppression by telling everyone to adopt your particular brand of tunnel vision.

III. The Importance of Recognizing Intersectionality

Let me clarify about the “particular brand of tunnel vision” thing. I don’t think having tunnel vision is a bad thing. We all have our pet topics and that’s cool. Some of us are more focused than others. Studying popular culture is probably my main focus, but since I love cross-sections I also keep abreast of other topics such as feminist issues,

human sexuality, and general oppression work. I don’t think that this is inherently better or worse than someone who chooses one topic, or even a smaller subset of topics, to focus on.

In fact, I’d go one step farther to say that the only way I think we’ll ever have a chance at winning the battle against oppression (as much as one can “win” such a thing) is if we wage this war on multiple levels. I believe that every fight we fight — whether it be against domestic violence or raising our voices against the overabundance of “sexy girls who kick ass” in popular media — is a valuable one. I believe every stride we make, however small and however flawed, should be appreciated.

That doesn’t mean that we have no right to critique it, but rather that the critique shouldn’t be done from a “our time could be spent better elsewhere.” Maybe your time could be spent better elsewhere, but you do not speak for me. If what speaks to you is fighting sexism on a societal level and shelving popular culture, then that’s wonderful! I, for one, am glad that there are activist out there who tackle issues that I don’t have the time and/or energy for.

IV. If the Goal is Unattainable, Why Bother?

And we can’t just snap our fingers and change society. Nor will a small group of people have that large of an impact on the world, in this case. It’s a monumental, impractical and impossible task to attempt, that at this point in time will lead to failure, and then disappointment, resentment and anger over that failure.

No matter how many times I read this quote, all I can think of is, “Oh, come on. Let’s be serious here.” The same can be said of feminism, or civil rights activism, or, really, any cause where people struggle against the way society is. It’s an uphill battle with few victories, and if you’re fighting for the glory you’d just as soon be better off cheering from the sidelines because it ain’t gonna happen.

But, faliure as a reason why we shouldn’t fight for our pet projects? Faliure? I mean, sure, there are some days when I look at what we do to each other and feel that the cause is hopeless. My blogging doesn’t stop the misogynists. It doesn’t stop the feminist infighting. It doesn’t stop the sexualization of women, inside or outside of comics. And if that’s a goal I expect to attain then, yeah, I’m going to fail.

When I, and I suspect many other people who fight oppression in whatever form they like best, say things like “ending the sexualization of women in comic books” is a goal of mine, I don’t mean that it’s my expectation that I, personally, will lead the crusade that once and for all eradicates the way women are used and abused in comics. I’m pretty sure that’s not what Girl Wonder thinks either. That kind of goal is known as a “long term goal” — which means that it’s the ideal that we strive for with our activism. It gives us a common goal from which to form a community.

Maybe one day this community will be big enough to make an impact. Maybe it won’t. But it’s stupid to just give up on fighting for what you believe in because you might not be around to see the main goal come to fruition. And, really, if everyone thought like that then the goal wouldn’t come to fruition! Fighting oppression starts with education — education of ourselves and spreading the awareness to others. If even one person becomes more informed on the issue, and therefore less likely to unthinkingly endorse it, then haven’t we already won?

V. Conclusion

There is no one way to fight for what we believe in. There’s no one topic, no magic button to press to get where we want. We all push our way through life doing the best we can. And, yeah, we’ll make mistakes. We’ll let our anger get the better of us and we’ll hurt each other. And it should be talked about and it should be discussed.

Because, really, discussion is what we all need. We’re not always going to agree, and we’re not always going to understand why another person does something else. And, you know what? That’s perfectly fine. It’s not all thinking the same way that’s the goal, it’s learning to understand our differences and change ourselves so we can change society.

Mr. Hubbard envokes our “go focus on a real issue” argument here. He first of all makes the usual mistake of assuming that speaking out on one issue means that the person therefore cannot, and does not, involve themselves in other issues. Or “mistake,” I should say. I’m fairly sure that in Hubbard’s case, as well as many others, it’s a calcuated move aimed at making the activist look silly while painting the attacker as someone who is truly interested in the root of the issue. Too bad for Mr. Hubbard, it’s quite obvious that he chose the first relevant-looking news article he could find — revealing his argument to be the slap in the face it really is. (Pun intended.)

Mr. Hubbard envokes our “go focus on a real issue” argument here. He first of all makes the usual mistake of assuming that speaking out on one issue means that the person therefore cannot, and does not, involve themselves in other issues. Or “mistake,” I should say. I’m fairly sure that in Hubbard’s case, as well as many others, it’s a calcuated move aimed at making the activist look silly while painting the attacker as someone who is truly interested in the root of the issue. Too bad for Mr. Hubbard, it’s quite obvious that he chose the first relevant-looking news article he could find — revealing his argument to be the slap in the face it really is. (Pun intended.)

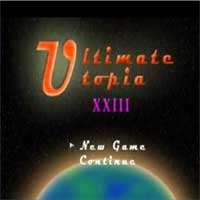

As is traditional with Squaresoft games, continuing a game in Ultimate Utopia will lead you to a character selection screen. The names for the three games are, respectively, Kyle, Danny, and Man. Kyle’s game has the characters we will learn to know and love, while Danny’s game seems to represent Grease (the area is called “Rydell High”), and Man’s game plays on the lack of diversity of Square’s NPCs – as all the characters in it are Man himself.

As is traditional with Squaresoft games, continuing a game in Ultimate Utopia will lead you to a character selection screen. The names for the three games are, respectively, Kyle, Danny, and Man. Kyle’s game has the characters we will learn to know and love, while Danny’s game seems to represent Grease (the area is called “Rydell High”), and Man’s game plays on the lack of diversity of Square’s NPCs – as all the characters in it are Man himself. As this flash movie is as much a parody of Squaresoft as it is a tribute, I was not surprised to find that Megan is the stereotypical magic user. Not just any magic user, however, but the physically weak healer. Her HP is a staggeringly low 191, as compared to the others who have anywhere from 954 to 1023. As the healer, her MP is the highest: 360, as compared to 54 (the highest MP next to hers). Her weapon of choice? The staff. It does 12 damage, yay!

As this flash movie is as much a parody of Squaresoft as it is a tribute, I was not surprised to find that Megan is the stereotypical magic user. Not just any magic user, however, but the physically weak healer. Her HP is a staggeringly low 191, as compared to the others who have anywhere from 954 to 1023. As the healer, her MP is the highest: 360, as compared to 54 (the highest MP next to hers). Her weapon of choice? The staff. It does 12 damage, yay!