I don’t think Joe Quesada’s a bad person. I don’t think he hates women. But I do think that he’s digging himself a deep, deep hole on this whole women in the comic book industry thing. For those of you not “in the know,” Joe Quesada is Marvel Comics’ Editor in Chief. This most recent kerfluffle involves him putting his foot into his mouth about the lack of women in the higher ranks of the comic book industry. Ragnell has the scoop on his mediocre response to the question “why hasn’t a women creator made it into the tight circle of Marvel creators?” in her post, Does This Sound Like An Answer?. More commentary can be found here.

Now, Quesada was clearly unprepared for the question. While it’s kind of an eye-roller, we have to cut him some slack. The rug was pulled out from under him, and he did the best he could. But, really, the slack is gone when he’s predictably asked to follow up on the question by Newsrama, and opens with something like this:

To think that the industry, Marvel, DC, or any publisher isn’t hospitable to female creators is ridiculous.

He follows that up with more excuses and backpeddling. He says everything, it seems, except that maybe, perhaps, possibly, the comic book industry might be a teensy bit, I don’t know… Oh, what word am I looking for?

Oh yeah, sexist!

Anyway, enough with the cheap shots. I don’t think Quesada is a bad person, I just think that he used weak arguments to excuse himself, and his colleagues, from examining the problem of sexism in the comic book industry.

I. Dismissing Claims of Hostility With Hosility

I’m going to go out on a limb here and suggest that the very fact that he chose a word like “ridiculous” to rebut the argument of hostility to women in comic books destroys his argument right off the bat. Calling something “ridiculous” is not simply disagreeing with it, it’s ridiculing the view as something that’s not worthy of discussion. That, I’d say, is a pretty hostile word. So, in essence, he’s rebutting the argument of hostility towards women in the comic book industry by being hostile towards the people who hold that view (who, I’d argue, are primarily women).

And, really, is Quesada — a male in a high position in one of the Big Two of American comics — really in a position to determine the answer to the hostility question? He’s in a position to disagree, sure. To offer counterarguments from the perspective of someone in the industry (and he does, which I will get to later), but saying “I disagree and here’s why” is a far cry from calling the problem “ridiculous.” The former opens the floor up for a discussion, the latter presents him as an authority on women in the comic industry. Which, I’m sorry, but he’s not. He can’t be, because he’s never had the experience of being a woman in the comic industry.

Before someone starts complaining that I’m trying to silence Quesada on the issue because he’s a man, let me clarify my position using a quote from a post on privilege I wrote:

[M]inority groups, coming from an insider perspective, are in a position to understand their issues in a way that privileged groups, as outsiders, never can. This does not mean that you must agree with everything a person from a minority says about that minority group’s issues, but rather that it’s important to remember that what’s theoretical discrimination for you is an inescapable part of their lives.[From How to be a Real Nice Guy by Andrea Rubenstein]

Quesada hasn’t experienced hostility for being a woman in the comic book industry because he isn’t one. He hasn’t seen it, either, because his privilege gives him the ability not to see it. This doesn’t make him a bad person, but it does add another dimension of stupidity to the way he chose to answer the question. By dismissing the potential validity of the criticism he is speaking from an authority that he doesn’t really have — it stops being about how he feels and starts being about him being Right and those who feel they have been discriminated against being Wrong.

II. Genderizing Talent

In order to back up his claim that a the comic book industry isn’t hostile to women, Quesada brings up the “genderblind” theory. I suppose the idea behind doing this is to stave off the claim that more men are involved in the industry than women, and more men are promoted over women, because of sexism. If he can prove a neutral environment, then it wouldn’t be his — or Marvel’s, or the comic industry’s, or society’s — problem, but rather the problem of the women submitting just not being good enough.

To that end, he brings up the subject of talent:

The beauty of comics is that in a sense we creators are faceless. [In comics] all that dictates the type of work you get is your talent. It doesn’t matter to us whether the person pitching a story is male, female, black, white, from some other country, or outer space, all we want is the most talented people on the planet.

I understand the theory behind that assesment. Two things matter about comics: the art and the writing. When you’re sitting there with a writing or drawing sample in front of you it feels all objective — it’ll either scream “talent!” or it won’t. But there are a few problems with that. Because talent is a highly subjective subject, it’s naive to think that it exists outside of socalized sexism.

Laura Q of the feminist SF blog explored this subject using Joss Whedon and race, but I think it’s relevant to the subject of sexism in the comic book industry:

There are lots of aspects to analyzing the “color blindness” fallacy, but there is one in particular which is significant to creators like Joss Whedon. Color blindness allows one to recognize talent, virtue, skill, beauty, in the ways that seem comfortable & familiar. It’s like just doing business over golf with the buddies — who just happen to be mostly/all guys. You didn’t mean to discriminate against women; it’s just that it’s fun and comfortable to do business with your friends, and your friends all look like you. To get beyond that, you have to push yourself out of your comfort zone, and unfortunately I think Joss doesn’t.

[From Joss Whedon & race by Laura Q]

Joss Whedon is far from a misogynist. He makes an effort to be sensitive of gender issues in his writing, tends to provide women with strong female role models, and he promotes the idea of equality not just through his writing, but in his public life as well. I’d say that he is a pretty pro-feminist guy. But familiarity is a powerful draw, and the idea of “talent” being an objective ideal is not one that’s questioned much in Western society.

And the comfort zone thing is alive and well in comics. I mean, when you have a prominent artist like Pia Guerra talking about how people praised her work by saying things like “you don’t draw like a girl,” I’d say that kind of kills the objectivity. But, really, is it any surprise when gender socalization begins at birth?

Then you add in the fact that you generally submit your name along with these samples, and that further skews the objectivity:

“The perception of a lot of older men working in comics is that women can’t draw,” [Colleen Doran] said. “The same men who see my work without my name on it are perfectly happy with it. After they find out I’m a woman, they start finding things wrong with it…”

[From Now Girls Allowed by Casey Franklin]

When all you ever hear is how comic books are for boys, and how women don’t like comics, and all that, is it any wonder that you would start thinking that women aren’t as good at drawing as men are? Not to mention that the most famous artists are men, so that further entrentches a paradigm of “talent = masculine.” When there is so obviously a gendered history to choosing artists — one that even those who have “made it” claim to have experienced — I’m not seeing how someone could argue the concept of talent as existing outside subjectivity in the comics industry.

III. Maintaining the “Boy’s Club”

After establishing that the methods for hiring are genderblind, Quesada needs to find a scapegoat for the lack of women in the top levels of Marvel and DC, so he falls back on the good old argument that women simply don’t read draw comics:

What I can tell you is that is that when I look at the pitches and art samples that we get, 99.9% of those pitches and samples come from males. I can’t control that, that’s just the law of averages, that’s who wants to submit.

Setting the “99.9%” hyperbole aside for the moment, I have no problem believing that the majority of pitches come from men. What I have trouble believing, however, is that it’s just the “law of averages” — putting it firmly out of the hands of Quesada and Marvel. Here again, Quesada is pretending that what Marvel publishes, and who it’s authored and drawn by, has no affect on the kinds of people who submit to their publishing house.

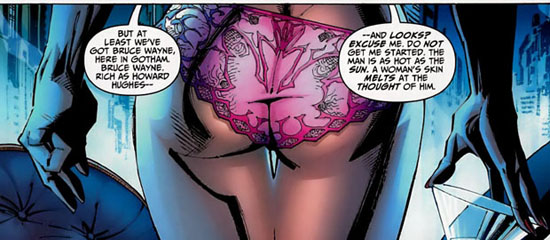

When it’s taken for granted that the mainstream comic industry is a bastion of sexism, that “99.9%” of readers are men (and, oh, have I’ve heard that ridiculous argument in terms of video games, too — people, majority does not = “99.9%”!), that most of the women are there to fulfill male fantasies… when you have all that, and more, perpetuated by the comics and comic book fans, don’t you think it’s a bit absurd to treat the issue as if it’s something that you can’t change? I’m sorry, but there’s no universe in which saying, effectively, “It’s out of our hands. The kind of people who submit has nothing to do with what we publish,” is anything but thinly veiled attempt to avoid changing one’s business practices to be more inclusive.

Which brings us to the last criticism I have for today, which is straight out of the “Anti-Affirmative Action” guidebook:

But, let me also add, that just because there is a lack of female writers doesn’t mean that we’re going to hand out a charity gig to a female just because of her gender. That to me defeats the purpose. As a father of an only female child I would want all doors open within whatever field my daughter decides to one day choose. But I would also want her to walk through those doors on her own merits, not on the charity of others or to fill some quota, and I suspect that when she’s old enough to understand that, she’ll feel the same.

The only situation this works in is going from the premise of a neutral society, which I don’t think is an assumption that can be made with any degree of accuracy. And, really, again alleviates him of having responsibility for choosing (directly or indirectly) who gets into Marvel and who moves up. It takes a subjective subject (who gets hired/promoted) and turns it into an objective one by utilizing the idea of Marvel as a pure meritocracy.

But, again, I don’t think that a meritocracy is a state that can be proved by any means. I believe that the theory that Affirmative Action utilizes is particularly relevant here:

The theory is that a simple adoption of meritocratic principles along the lines of race-blindness or gender-blindness will not suffice to change the situation for several reasons:

- Discrimination practices of the past preclude the acquisition of ‘merit’ by limiting access to educational opportunities and job experiences.

- Ostensible measures of ‘merit’ may well be biased toward the same groups who are already empowered.

- Regardless of overt principles, people already in positions of power are likely to hire people they already know, and/or people from similar backgrounds.

During this post I believe I have, at the very least, cast doubt on the evidence that Quesada uses to support his argument of a meritocracy. I have linked and quoted the experiences of sexism that women in the industry have encountered, which establishes a history of discrimination that may, in fact, continue to have an impact on hiring practices today. I have discussed how the concept of “talent” that Quesada puts out there as “genderblind” is a subjective concept, and therefore may be subject to the same pitfalls that we experience as a culture. And the final point — that of familarity — is, really, what started all this. Marvel and DC are both, for the most part, self-perpetuating “boys’ clubs” who, for various reasons, are reluctant to examine the lack of women in their ranks.

IV. Conclusion

Quesada had over a week to consider how he was going to frame the conversation on the lack of female creators in the higher positions of Marvel. Instead of spending that time reflecting on the seriousness of the question, and asking himself how he — as a person of power in one of the largest comic companies in America — could help be part of the solution, he chose to dismiss the argument out of hand. His reaction was primarily a defensive one and because of that he neatly avoided engaging in a critique — of himself, his company, and comic book culture in general.

As the Editor in Chief of Marvel, Quesada is in a position to do a lot of good in terms of helping to address the imbalance of gender (and other minorities) in his company. Unfortunately, as long as he is afraid to engage in a little self critique things are going to stay the way they are. And, let’s face it: it’s a lot easier to wring your hands and say, “There’s nothing we can do! Women just don’t submit enough comics! Those who do just aren’t good enough to work on our large projects!” than it is to admit that there’s a problem with your company, especially when it’s not one that’s easily solved.

Thank you, thank you for writing this. When I first came across the Quesada comment, I was pissed but also thought that he just didn’t think about the issue before because of his own privilege. I was curious to see how he’d react to the criticism and was appalled by what he said and how he justified it.

I just about threw all my X-Men comics out the door.